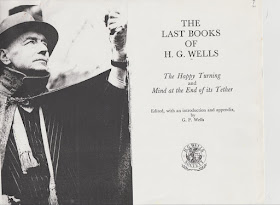

So, just about the time I moved out here, over twenty years ago now, I read a compilation of two little books by H. G. Wells that between them represented his final thoughts on the fate of humanity. Having recently come across the photocopy of this I made at the time, I thought it'd make for an interesting re-reading.

Wells was a meliorist, which is to say that he believed that by working together it was possible, little by little, to make the world a better place (say, by medical research leading to vaccines or improvements in agriculture; things that improved quality of life). It was slow and hard but real progress was possible.

Writing in the last months of World War II, at a time when he was nearing eighty, suffering from cancer, and living in bomb-torn London,

he decided he'd been wrong. In particular he laid a good portion of the blame on 'the necessity common minds are under to believe they have natural inferiors, of whom they are entitled to take advantage' (.11).

His response to this was twofold: one lighthearted whimsical little work and one a pessimistic prediction; the juxtaposition of their dating from about the same time makes them interesting.

THE HAPPY TURNING

In the first of these two little books

he celebrates escapism through dreams: 'this delightful land of my lifelong suppressions, in which my desires and unsatisfied fancies, hopes, memories and imagination have accumulated inexhaustible treasure' (.22). Wells embraces not what Tolkien wd call the eucatastrophe of a Happy Ending but what he dubs the Happy Turning of a compensatory dream.

Wide ranged and rambling as this brief little book is, the best parts were Wells' depiction of old age as a time of falling into habits* and the two chapters in which Wells dreams of conversations with Jesus --part five: 'Jesus of Nazareth discusses his Failure' and part seven: 'Miracles, Devils and the Gadarene Swine' (particularly his take on the miracle of the loaves and fishes). The tone of these exchanges reminds me more of Blake (THE MARRIAGE OF HEAVEN & HELL) than Lewis (THE GREAT DIVORCE, written at about this time).

The strangest part, by far, is his chapter devoted to cursing sycamore trees. That the book is rambling, not to say weird, is one of the things that marks it as one of those books a writer writes purely for personal satisfaction.

MIND AT THE END OF ITS TETHER

Much more focused, and rather less interesting, is its companion piece, in which Wells announces that humanity, having had its chance, is now headed to extinction. A new species will replace us, which may be descended from homo sapiens or might be wholly unrelated. There's nothing we can do, Wells believes, to avoid this fate. He counsels what at first looks like a form of existentialism but is more probably stoicism: that we each meet the end with what dignity we can muster.

The two approaches, which the book's editor finds diametrically opposed, are in fact easy to reconcile if we take them in reverse order and assume that the withdrawal into dreams is one example of an individual's facing extinction (of individual and species) on his own terms.

So there it is: a great reformer turns in the end, at the end of his tether, to the cold comfort of stoicism and the warm comfort of dreams, and between them still has the wherewithall to engage in a little whimsey. It's as if Tolkien and Lovecraft collaborated on a project: the result wd no doubt be interesting but unsatisfactory.

--John R.

--current reading: Wells, THE MIND AT THE END OF ITS TETHER (#II.3549; a rereading; just finished)

*part 1: 'How I came to the Happy Turning' (.21-22). Wells' description of of his life sinking down into a repertoire of a routine of several favorite outings may strike a cord with those experiencing encroaching age or persistent ill health (I particularly liked the bit about baiting one walk with a visit to a bookstore). All in all, I thought it was the best thing in this little book, the one sign that the author of 'The Truth about Pyecroft' and similar stories had not altogether lost his touch:

In my daytime efforts to keep myself fit and active,

I oblige myself to walk a mile or so on all days that

are not impossibly harsh. I walk to the right to the Zoo,

or I walk across to Queen Mary's Rose Garden

or down by several routes to my Savile Club, or

I bait my walk with Smith's bookshop at Baker Street.

I have to sit down a bit every now and then, and that

limits my range. I've played these ambulatory variations

now for two years and a half, for I am too busy to go

out of town, out of reach of my books . . .

I dream I am at my front door starting out for the

accustomed round. I go out and suddenly realise

there is a possible turning I have overlooked!

And in a trice I am walking more briskly than

I have ever walked before, up hill and down dale,

in scenes of happiness such as I have

never hoped to see again . . .